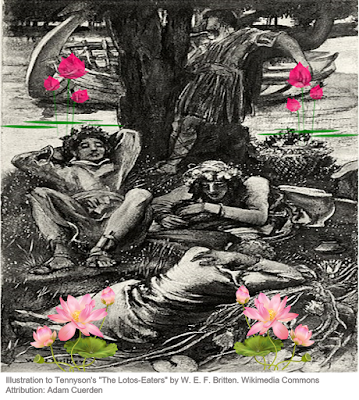

Ten years of conservative government has culminated in a lack of preparedness for the onslaught of a virus pandemic, or indeed any crisis. The TEFS posting of the 26th February looked at the situation Ofqual finds itself in with ‘The next labour of Ofqual is announced’. The final battle was fought last year, and the system failed. In an Education Committee hearing this week, the Schools Minster, Nick Gibb shrugged this off with “we do not design an exam system for pandemics”. But this is at the core of the problem and smacks of the complacency of the Lotophagi (Lotus-Eaters in the image). Complacency and poor planning allowed the new coronavirus to sneak in unnoticed like a Trojan horse. The resulting total chaos of the examinations last summer marked defeat for the Department for Education, the government, and its examination policies. Its effects only became apparent after it was already too late. Now, the government and Ofqual are trying to find a way to return home to the old order after the defeat of last summer. But it could take the next ten years to reach home only to find it changed for ever. It is time to wake up and move on.

The Parliamentary Education Committee raised many important questions this week in its latest hearings on ‘The impact of COVID-19 on education and children’s services’. The answers were confused and logically inconsistent in many areas in a 2 hour and 11-minute session online. Most of the questions were directed at the Schools Minister, Nick Gibb, who was accompanied by the recently appointed acting chair of Ofqual, Ian Bauckham, and acting Chief Regulator, Simon Lebus. Despite their experience, they have had little time to settle in.

The double act of Conservative Robert Halfon in the chair and Labour MP, Ian Mearns, worked well and exposed a confused minister. This exchange of less than three minutes is a good example of the current situation. Teachers will be mightily confused along with the rest of us.

The full hearing is on video here and the transcript here:

The overall conclusion is that the Department for Education is seeking a way back to a system that has comprehensively failed. There was even more emphasis on the accepted ‘fact’ that examinations are the fairest way to assess students. This is despite Ofqual’s own admission that their assessment methods are unacceptably unreliable with one in four grades incorrect (See TEFS 11th December 2020 ‘Accuracy, reliability and the ‘William Tell’). There are many critics calling for change. In a highly critical posting, ‘No, Minister. England’s school exams are not ‘the fairest way’ (London School of Economics 20th November 2020), Dennis Sherwood maintained his pressure on the existing examination system that Ofqual is so determined to defend. Schools Minister, Nick Gibb did not break ranks and pushed on with the notion that a single examination at the end of two years was the best way to assess students. This is not the case as the pandemic effects have proved.

Examination system not designed for a pandemic.

The decision to push most of the assessment for university entrance onto final examinations at A-level led to problems last year in making judgements based on earlier work. This became government policy back in 2014 under Education secretary, Michael Gove who wanted “a greater focus on exams rather than controlled assessment” in an effort to counter grade inflation. It looks like a very bad idea in hindsight. TEFS has called for a radical overhaul of the A-level system in the light of this and recently proposed wider assessments and decisions about university entrance a year earlier as happens in Scotland and Ireland (see TEFS 15th January 2021 ‘A radical overhaul of examinations is needed as soon as possible’).

Grade inflation and student numbers.

There was considerable confusion on the issue of even more grade inflation rising above the results of last year. None of the issues were resolved by those being questioned. The system now being rolled out appears unregulated and will be prone to higher grades being awarded. The checks envisaged could descend into greater chaos. The Sun put it well describing the situation as the ‘Wild West’. One thing is for sure, the government will be forced to impose a cap on student numbers to avoid the rising costs of more loans. This might be a simple number cap or imposition of minimum grades as proposed in the Augar Review. The implications for students affected by disadvantages at this time are serious.

Algorithms have not gone away.

The problems last summer stemmed from the use of an algorithm to adjust the spread of grades for different schools and colleges based on their previous record. It ignored individual students efforts and it was doomed from the start. This was pointed out in plenty of time by Jon Coles, former director general of the Department for Education, in July 2020. He wrote to the Education Secretary, Gavin Williamson, warning that Ofqual’s grading system would lead to unfairness in the system. Later the same month, the Education Committee warned about the algorithm, saying that it risked inaccuracy and bias against young people from disadvantaged background ( ‘Getting the grades they’ve earned Covid-19: the cancellation of exams and ‘calculated’ grades’ ).

However, it is clear now that schools and colleges will each have to adopt their own algorithm to remain consistent with past results. These will be checked for consistency. Thus, a single algorithm across the system will be replaced by a multitude of algorithms. The reason for this is the fear of spot checks that might uncover inflated grades and adversely affect their results. Halfon was persistent in asking about ‘spot checks’ on schools and failed to get a full answer. However, Gibb also indicate that the extent of the checks “will depend on resource and time”. It doesn’t inspire confidence as so called ‘sharp elbowed’ parents push teachers for higher grades. Teachers are in a difficult position after already submitting predicted grades for university applicants to UCAS at the end of January. Falling back from these will prove difficult.

Halfon also quoted Jon Coles “If ‘no algorithm’ is taken to mean ‘no use of past data’ and ‘no exams by the back door’ to mean ‘no common assessment taken under standard conditions’, then we really are lost…….. He is not somebody who would want to ignore those children who have had minimum learning, as you describe. Could you comment on what he says?”. The response from Gibb was simply “Yes. He is a distinguished educationalist”.

All must have prizes and adventures in wonderland.

This educational idea of ‘all must have prizes’ was introduced by Halfon in the context of the minister’s earlier comments to the committee, “In opting for this system, it is a dodge tactic. I know when you came to our Committee a few weeks ago, you quoted E. D. Hirsch. Is this an “all must have prizes” approach to exam grades? You have transmogrified from E. D. Hirsch to “all must have prizes.”

Hirsh is an established educationalist and humanist from the USA who is a vociferous critic of the way education has strayed. In his 1996 text, ‘The Schools We Need and Why We Don't Have Them’, he argues that too much emphasis on how children learn, instead of teaching ’facts’, is doing damage to education. However, the origin of the quotation to do with education might have come from elsewhere. Hirsch’s ideas were put in the context of the UK by Melanie Philips in 1998 in her book ‘All Must have Prizes’ . This work has rightly come in for very strong and valid criticism. However, there is a suspicion that our government ministers have been influenced by its arguments.

For the rest of us, the term originated from the Dodo in ’Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ who declares at the end of the race that “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes”. Upon Halfon saying this, it seemed he was calling Gibb a Dodo. One who was telling Ofqual (Alice) to give out the prizes to all and take one for herself. Of course, “Alice thought the whole thing very absurd, but they all looked so grave that she did not dare to laugh”. Remember that the author was the mathematician Charles Dodgson and he might have had another view of the balance of education falling somewhere between understanding versus learning facts.

Horses for courses.

It seems to me that different subjects and disciplines have different ways of working and a ‘one size fits all’ system of teaching and examination would not work well every time. But the committee composition itself exposes a shortfall in perception of this issue. Only Caroline Johnson, who is medically qualified, and Ian Mearns, who has a non-university technical background, could claim to have a scientific view. The fact that the other people present at the hearing have no background in science is of great concern. This leads to a ‘blind-spot' in perception of education that should be acknowledged more. My experience is in science teaching at university. Science education is incremental in how it develops. Universities must build upon pre-existing understanding and knowledge. Gaps in knowledge can be filled and the coming years will see more of this in first year university courses. However, fixing gaps in understanding may prove impossible. Emphasis on growing an attainment ‘tree of knowledge’ at the expense of progression in understanding will not bear fruit. An examination and assessment system must take account of this. The hope is teachers will be able to bring all this together in making their judgments. Their role must be allowed to continue into the future.

Meanwhile the attainment gap widens.

An excellent review by the Education Endowment Foundation this week, ‘Best evidence on impact of Covid-19 on pupil attainment’ (updated from June 2020 on 9th March 2021), concluded “there is a large attainment gap for disadvantaged pupils, which seems to have grown”. This is not surprising as many of these students will have not been able to fully engage. Others with better resources may even find they have done much better from home. The inequalities will not go away easily.

This is clearly a growing problem and the impact will be greater depending on the subjects studied. Even small gaps in understanding in science will be magnified later as students struggle and lecturers fail to spot the source of the confusion. It is a bit like putting a vehicle on the road with some wheel nuts missing. You only become aware when the wheel falls off on the motorway. Recent research has indicated that the gaps are widening in mathematics and science due to the COVID-19 crisis (see GL Assessment February 2021 ‘Impact of Covid-19 on attainment: initial analysis’). The implications for universities are significant and it will take a major readjustment of assumptions to rectify.

The way forward.

Instead of seeking to make their way back home to a past that has had its day, the government must seek to start anew. TEFS has called for a radical overhaul of the assessment system to bring it closer to the systems in Scotland and Ireland (TEFS 15th January 2021 ‘A radical overhaul of examinations is needed as soon as possible’). Decisions on suitability for university degree courses or otherwise should be moved forward by a year and allow more time to be taken for a better-informed decision on university choices post qualification. A mad post qualification admission (PQA) dash in the summer after an ‘all or nothing exam’ looks insane.

Yet the Department for Education and the Government appear to have stopped trying. They have sunk into a sleepy assumption that all will somehow return to the past. They have become like the mythical Lotus Eaters who need to wake up to the challenges coming. Everyone may be tired, but now is the time to grasp the chance to build a genuinely fairer system and not settle back into a complacency that expects things to return to the same old unfair ‘norm'.

Surely, surely, slumber is more sweet than toil, the shore

Than labour in the deep mid-ocean, wind and wave and oar;

O, rest ye, brother mariners, we will not wander more.

The Louts-eaters, Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Mike Larkin, retired from Queen's University Belfast after 37 years teaching Microbiology, Biochemistry and Genetics. He has served on the Senate and Finance and planning committee of a Russell Group University.

Comments

Post a Comment

Constructive comments please.

Did you have a free Higher Education?