A series of reports from the UNESCO Centre at the University of Ulster this week coincided with the setting up of a new independent review panel to look at the divided Northern Ireland education system. The selection test, or 11+, used for secondary school selection dominates the media coverage. With tests cancelled for the 2021 intake due to COVID-19, there is increasing pressure to abandon them or make major reforms. The socioeconomic divisions caused are also put to the test. These are compounded by two parallel systems running along sectarian lines. So called ‘integrated’ education is advancing slowly and has a long way to go. Reforms of GCSEs and A-Levels will also enter the equation and could precipitate a greater seismic shift. There will be considerable support for the status quo from those who benefit, and nothing will shift without greater public confidence. However, the time is right to redouble efforts to make the system fair and equal. Increasing numbers of children from migrant families are falling between the cracks and change must be fully inclusive. It must be remembered that pupils and young students are the most important stakeholders who should be consulted first.

This week saw the release of more detailed and comprehensive reports on education in Northern Ireland by researchers at the UNESCO Centre in the University of Ulster. The reports in ‘Transforming Education in Northern Ireland’ are a detailed analysis of school education in Northern Ireland. (Please note that as of today the report has been offline). Essentially, it is a synopsis of twelve briefing papers, ‘Transforming Education’, released between April 2019 and March 2021. These cover topics such as the career paths of teachers, impact of community division, religion and education, duplication of provision, school governance, parental choice, administration, and school travel. However, it was the briefing ‘Academic Selection and the Transfer Test’, released this week, that attracted the attention of the media. It was reported by the BBC on Tuesday as Transfer test: Academic selection 'traumatic', new research claims. The transfer test (aka the 11+) is the first major pivot point in the education of children that determines how they progress. The second pivot happens to young students at sixteen when they sit GCSEs. The results determine progression or not to A-levels and beyond. Both pivots set students up for failure. They cause anxiety and fear of failure, and no platitude can hide this.

One caveat is that the reports were supported by the Integrated Education Fund. This was established 1992 to “bridge the gap between the limited government money available for integrated schools and what was actually needed”. The neutral charities, ‘The Community Foundation Northern Ireland’ and ’The Ireland Funds’, are also acknowledged for their support.

Timing is everything.

There is no coincidence about the reports from the team at the UNESCO Centre emerging this week. They were timed to coincide with the setting up of another review of education in Northern Ireland. In January 2020, the main parties agreed a ‘New Decade, New Approach’ across a range of key policies. Education features as a high priority on the agenda and heralds a possible change of direction “To help build a shared and integrated society”. A review was promised, and its aim will be to “focus on securing greater efficiency in delivery costs, raising standards, access to the curriculum for all pupils, and the prospects of moving towards a single education system.” Of particular concern is the “persistent educational underachievement and socio-economic background, including the long-standing issues facing working-class, Protestant boys”. This is a special concern of Education Minister, Peter Weir who has raised this many times. Of course it is a common problem across the UK for all boys from disadvantaged backgrounds who are the least likely to make it to A-levels (Sutton Trust, November 2015 ‘Background to success’)

An expert panel was set up in Northern Ireland last year to advance the policy. Its members are almost all from Northern Ireland and their survey of the views of stakeholders from October 2020 has yet to report. The results will no doubt feed into the deliberations of the new ‘external independent’ panel this year. Moves to set up this panel are well advanced with a closing data for applicants today. They will have a major task to get their heads around the peculiar system that exists in Northern Ireland. They will observe there is a pronounced vertical stratification based on social advantage involving grammar schools and a transfer test. But an added complication is that the system runs down parallel tracks dominated by the sectarian divide. So called ‘integrated’ education is making the boundaries less sharp over time but it is slow to take hold. Despite the ongoing political divide across the province, it seems there is some agreement. Both sides have evolved the same educational modus operandum.

The transfer test pivot.

Transfer to secondary school is stressful for children at the best of times. Add the transfer 11+ test to the formula, and the concept of failure is foisted upon children for the first time. The conclusion that fear of failure or acceptance of failure is traumatic comes as no surprise to anyone who has experienced it. The academics at the UNESCO Centre join most educationalists in condemning selection at this point. They stress this for good reason with “It is traumatic for many children, creating damage which often endures into adulthood. It often distorts the curriculum of children in primary and post-primary schools and achieves little other than protecting the advantages of a few”. My experience, between 1963 to when I sat the 11+ in England in 1965, was one of fear. A former primary school teacher who lived nearby tutored me and my brother for free to help us. Despite doing well throughout, I reached even higher levels of anxiety that impacted me badly at every examination that followed. I attended a good grammar school but had a long commute across the city every day. The stress of that journey, along with exam anxiety, meant it was a bad time best forgotten.

Yet, despite being abandoned across most of the UK from 1976, the test remains a major pivotal point in the education of children in Northern Ireland. A few grammar schools persist in England and still use a selection test. However, in Northern Ireland all the grammar schools survived with selection tests despite efforts to abandon them. The reasons for this lie with those who believe they benefit. This idea dominated the Northern Ireland government from 1947 to 2008 when the last official transfer tests were held.

The writing was on the wall for the transfer test in the fallout of a ground-breaking report from Queens University and the University of Ulster in 2000 (Gallagher, T and Smith A (2000) The Effects Of The Selective System Of Secondary Education In Northern Ireland). This was followed a review in 2001, known as the Burns report (Report of the Review Body on Post-Primary Education), that recommended “The transfer tests (11+ tests) should end as soon as possible”. In 2004, the Costello report (Future Post Primary Arrangements in Northern Ireland) firmly reinforced this aim.

However, it took until 2008 for the test to be abandoned, at least one regulated by the government. Instead, it became a bit like a ‘wild west stand-off’ between two rival factions and the sheriff.

The stand-off.

The lack of an official transfer test did not deter the grammar schools across the divide. They simply ploughed on with their own ‘unregulated’ and independent testing despite government guidelines that specifically stated, “Decisions on admissions should not relate to academic ability”. This proviso had an unfortunate sting in its tail and tests were then skewed toward educational attainment and not ability. The guidance also stressed that “Primary schools must not depart from their statutory obligations to deliver the curriculum and should not facilitate unregulated tests in any way”. The result was pressure on teachers to coach children, an explosion of expensive private tutoring for those who could afford it, and warnings issued to schools. By 2016, the government relented with guidelines issued to primary schools allowing them to “Carry out preparation for tests during core teaching hours and coach pupils in exam technique”. It also allowed grammar schools to adjust their tests to “use academic selection as the basis for admission”. The result was a ‘dog’s breakfast’ of a system that confused many parents and accentuated the social stratification in education.

There are two excellent reports by researchers at the Northern Ireland Assembly. ‘Education system in Northern Ireland’ (2016) addresses the historical context and ‘Academic Selection’ (2020) the journey to the situation today.

A dog’s breakfast and no reasoning.

Since 2016, the idea of a transfer test based on attainment and not ability has become entrenched in the system and will be difficult to dislodge. Many outside Northern Ireland will also not understand the parallel evolution of two tests along the sectarian divide. Firstly, there is a test organised by the Post-Primary Transfer Consortium Ltd. (PPTC). This is a GL administered assessment and is run for the 33 Catholic grammar schools. Secondly, running alongside is the Association of Quality Education (AQE) test run for 34 of the ‘other’ grammar schools that are defined in Northern Ireland as the ‘Protestant’ grammar schools (noted in the NI Assembly report ‘Academic Selection’ (2020)). To avoid the idea that the tests are based on ability, they exclusively focus on measuring attainment achieved in Key Stage 2 Maths and English. It seems somewhat ironic that ‘reasoning’ was abandoned.

Interestingly, with the Education Authority (EA) washing its hands of transfer tests, it became difficult for parents to see what was happening or what to decide. So much so that the Belfast Telegraph provides practice papers ‘Northern Ireland Transfer Tests 2021: Get your AQE and GL style practice papers’. It also means there are no official government statistics. So the Belfast Telegraph again stepped in and publishes the results from an annual survey of schools (The 2019 and 2020 results are in ‘Belfast Telegraph transfer test guide reveals scores accepted by every Northern Ireland school’).

What is the transfer 11+ test anyway?

This is lost in the mists of time for most people in the UK. A mythical fireside story told by grandparents who barely understood what was happening to them in the first place. In answer, it is whatever test you want it to be. There is not one single type of test. In Northern Ireland, it was mostly based on attainment and avoided too much emphasis on testing for ability. I sat with primary school teachers and other parents in a meeting about the test in 2002. At that time, it was a test sanctioned and operated by the state. A video presented by a well-known and highly respected local TV reporter was the centre piece. She calmly announced “Remember this test is not about your child’s ability. It is about their suitability for a grammar school education”. It took a while for this to sink in with the parents, but I was struck by the brutal honesty. There was a mixture of shock and indignation in the room. Every parent, other than me, appeared to be tutoring their child in the mistaken belief that they could buy more ability. The teachers stressed this was not needed. We simply had to ensure plenty of extracurricular reading to hone their comprehension. The rest would follow. My take at the time was that the test problems were indeed easy but often caged in the context of complex text. If the text could be comprehended, then the problems were easier to resolve. There was an element of reasoning included that would give some idea of a child’s ability. But as it stood, tutoring could yield better results.

This was the situation up to when the official transfer 11+ test was abolished in 2008. The move to using only Maths and English in unregulated attainment testing after that simply made matters worse.

The impact of COVID-19 learning loss.

The ongoing COVID-19 crisis since last year has exposed the inherent problem in using a transfer test. Despite lockdowns and children losing teaching time, schools and parents seemed determined to press on with the tests in November. They were postponed to early 2021 and then had to be abandoned. This forced schools to revert to a range of different admissions criteria. This led to some cutting parodies that were very close to the bone, such as this video shared on Facebook earlier in the year. One serious criterion was to only consider children who had been entered for the test last year. This was a simple expedient based upon knowing that only about half of the eligible primary school children are put forward for the test by their parents. This may be fine for the 2021 intake, but something else will be needed for 2022. A review now may conclude, like those before, that there should be no test. Indeed, some schools are now joining others in abandoning selection tests for the 2022 intake. An alternative could be to insist on a move to a reasoning based test that could bypass the effects of loss of learning. Sure enough, this has been proposed. The BBC reported (BBC 3rd March 2021 ‘Schools consider 'radical change' to transfer tests’) that PPTC had proposed in a discussion paper that “Serious consideration should be given to moving away from an Entrance Assessment which is attainment based to one which is aptitude based". This would entail a move to exclusively using verbal and non-verbal reasoning questions. I suspect parents who have invested in tutoring for an attainment test will not want to face the uncertainty and more schools will be forced to scrap the test entirely. AQA will also have to make a move, but they might wait, along with schools, to see how many parents register their children for the test over the summer before deciding. As there is a fee involved, everyone should surely be informed of the nature of the test well in advance.

How did abolition of the transfer 11+ test affect schools, social division, and integration?

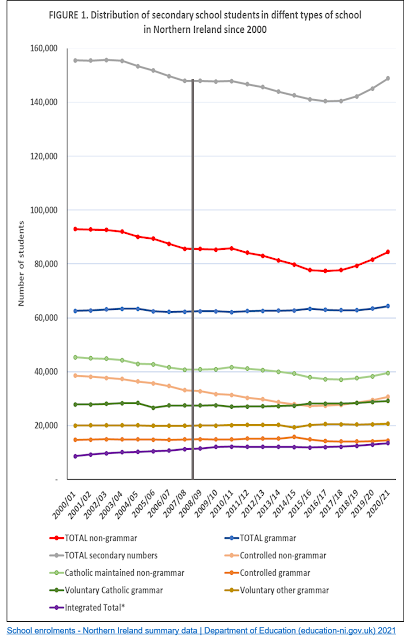

The answer is simple, there was little or no effect on social division or on progress in integration. Looking at the data presented in Figure 1, it becomes clear to observers that there is a parallel track that survived the attempt to abolish the test in 2008. The figure is adapted from the latest Northern Ireland Department of Education data releases (School enrolments - Northern Ireland summary data | Department of Education (education-ni.gov.uk)). The transfer test still led to a stark divide with around a third of children going onto grammar school (red and blue lines). These are further divided into those attending ‘Catholic’ grammar and non-grammar schools (green lines) and largely ‘Protestant’ non-grammar controlled schools and maintained or voluntary controlled grammar schools (amber lines).

Integrated schools have been gradually exerting their influence. These are divided into those controlled by the state and voluntary schools. The totals for both are shown here (purple). It seems that their student numbers are rising slowly at the expense of the controlled non-grammar schools. An integrated school is expected to enrol at least 30% Catholic of Protestant students; however this rule is not applied strictly. It may be that some parents are not so wedded to integration but think their children have a better chance in such a school compared with state controlled non-grammar schools.

'Newcomers' fall between the cracks.

‘Newcomers’ is the term used to describe children of migrants coming into Northern Ireland. Largely this means they arrive with English as a second language or no English. They seem to have become a blind spot in the vision of the government and the they are being excluded as a result. Their experiences are often challenging (Feels like Home - Experiences of newcomer pupils in primary schools in Northern Ireland 2015.pdf (barnardos.org.uk)) and the increasing numbers presented in Figure 2b show how the challenge is growing.

Most alarming is the observation that the vast majority fail to get into a grammar school as shown in Figure 2a. Sitting at only 12% in 2021 it has declined from 41% in 2005 before the transfer test changes. Prior to the Education Authority (EA) forming in 2015, education oversight was devolved to five Education and Library Boards. While a state transfer test was in place, they could offer support for ‘newcomer’ students by assessing their ability outside of the test. This made access to grammar school more feasible and assisted parents trying to adjust. However, with no state involvement since, or support for the test, there is no alternative in play. The EA offers some support to schools for ‘ newcomers’ but there is nothing noted about the transfer test. Grammar schools acknowledge this and have policies for exceptional circumstances. However, these vary across schools. The onus is on parents to provide evidence and seek out support from primary school teachers. This obstacle leads to an inevitable shortfall in ‘newcomer’ students making it to grammar school. It is one aspect of the failure of government that should be addressed with urgency.

The status quo or breaking the mould.

The situation in Northern Ireland has not come about by accident. It is the result of a long history of political conflict. A high degree of suspicion and mistrust persists across most sections of society. Reaching a high enough level of public confidence to foster change is no trivial matter in this febrile environment. All political changes are coloured in terms of advantage to one side or the other. However, to many the educational status quo represents a sensible compromise that somehow works. The UNESCO team at Ulster University argue that this is inefficient and leads to costly duplication. However, this conclusion may not be so simple. On an overall scale, the latest data (primary and secondary schools and excluding nursery schools) indicates a fair degree of comparability across the UK. In Northern Ireland, there are 304 pupils per school on average. England may seem more efficient with 365 per school. Wales is similarly placed with a mean of 317 per school. But Scotland is an outlier with 283 per school. Of course, this does not look at the distribution per school and their locations. Urban schools are likely to be bigger since they can draw on larger numbers in their region. Isolated rural schools may have smaller numbers but must be kept open to avoid long travel times for children. Therefore, the difference in numbers per school is more likely to correlate with the extent of urbanisation in each jurisdiction and the extent of population dispersal in remote areas.

Those advocating integrated schools may see closure of some schools as part of the solution but, with student numbers rising, this would seem unnecessary. Instead, there would have to be conversion of more schools to integrated status. The voluntary grammar schools might consider this since many are not exclusively serving ‘protestant’ students. This is less so for the state-controlled grammar schools. The last to hold out are likely to be the voluntary catholic grammar schools. But, even if this happened, their intake would be unlikely to change allegiance.

Does the status quo work?

It seems to work because it must. In terms of progress of students in secondary schools, it could be argued that the system, however strange it appears, is still working as students progress. The latest data on exam performance in schools reveals some interesting anomalies. Assuming a rigorous transfer test did its job efficiently and fairly, then one might assume this would be clearly borne out on GCSE and A-Level results day. However, this is not clear cut.

The latest school performance data for 2018/19 (this process was suspended for 2019/20) reveals that 94% of grammar school students achieved at least 5 or more GCSEs at grade A*-C (or the equivalent in the numbering system used by English Exam Boards) including English and mathematics. This would be a suitable standard for going onto A-levels, however some grammar schools expect more. Surprisingly, in non-grammar schools a creditable 55% of students reached this level and would also be suitable to go onto A-levels.

At A-Level, the gap narrows further and 58% of non-grammar school students achieve 3 or more A Levels at grade A*-C. This is not so far behind the 72% in grammar schools.

It would seem the system is flexible and able to right itself for many students in time. Failure in the transfer test is redeemed by a sizeable number of students who succeed later. For others, success in the transfer test, that was fuelled by tutoring and a false indication of ability, becomes a costly illusion.

The second pivot point.

Getting the right number of high-grade GCSEs is a clear pivot point in the future all school students. Success leads to A-levels and further progress. With many students succeeding after failing the transfer test, this could mean they are much more influential in the outcome.

As a result, grammar schools might prefer to hide from parents their policy of setting strict standards for entry to their sixth forms. One leading Belfast grammar school ‘boasts’ that over 80% of its students achieve high enough GCSE grades to enter their sixth form. But this leaves nearly 20% left out of the school. The simple fact is grammar schools readily accept successful students from other schools. This dilutes the performance of other schools further and the rankings are somewhat skewed as a result. However, the positive side is that the best students have a choice to change school and iron out the wrinkles caused by the 11+.

A seismic shift in direction.

The system has evolved to its current position for a reason and making changes will be an exercise in compromise. However, the COVID-19 crisis still could be a rumble deep underground that has yet to surface. Many see the final demise of the transfer test as the biggest change likely to come about because of school closures and transfer test cancelations. Most parents will no doubt resist an alternative ability-based test emerging as they fear the outcome. This may only become a tremor as schools adjust position. However, other changes in assessment at a later change could be a major earthquake.

If the government was to look for a seismic shift in the direction of schools and the routes taken by students, it might consider the radical change proposed by TEFS in January with ‘A radical overhaul of examinations is needed as soon as possible’. The other jurisdictions across the rest of the UK are looking again at how robust their examination system is in the light of cancellations. There has to be some reform, particularly to A-levels. The crux of the TEFS argument is that exams that select for university entrance will have to be moved forward by a year to avoid the chaos of post qualification admissions in England and Wales. This would align the exams more closely with what happens in Scotland and Ireland. Doing this would set up a tsunami that would surge back to GCSEs and ultimately drown the transfer test in Northern Ireland.

In the event of the governments in England and Wales not seeing this option as viable for them, Northern Ireland might look elsewhere and closer to home. A post-COVID collaboration between Scotland, Ireland, and Northern Ireland on examinations would be a fresh start. After all, the systems in Scotland and Ireland are respected and already have many features in common. Breaking away from the ‘English inspired’ exams, that must be mirrored in Northern Ireland, would mean a fresh start. Proceeding with a revamped common system could be enough to break the impasse that divides students and schools.

Making such changes would be a huge departure from the past and they will not be easily done. In the end, the confidence of people must be in place for this to happen. In the deliberations to follow, it would be churlish for anyone to declare they have a solution that is best and try to impose it. Sometimes the principle ‘if it aint broken, don’t fix it’ offers the best option. Many ‘stakeholders’ will pitch in with different ideologies and alternatives. However, caution must be exercised. It is sometimes forgotten that the pupils and young students are the real stakeholders. A good starting point would be to agree that their interests and fairness must come first.

Mike Larkin, retired from Queen's University Belfast after 37 years teaching Microbiology, Biochemistry and Genetics. He has served on the Senate and Finance and planning committee of a Russell Group University.

Comments

Post a Comment

Constructive comments please.

Did you have a free Higher Education?